- Avarna Jain,

Chairperson RPSG Lifestyle Media

Aanchal Malhotra on the Heirlooms and Keepsakes That Keep Memories Alive

The author explores the objects that carry memory, history, and personal stories across generations...

Aanchal Malhotra explains how heirlooms carry memory through time.Aanchal Malhotra

Oral historian and author Aanchal Malhotra has long believed that memory lives not only in the stories we tell but also in the objects we keep. And through her personal archiving and research, Aanchal focuses on the significance of everyday belongings that carry fragments of history, migration, and emotion.

Whether it’s a trunk that was taken along during partition or jewellery passed down over generations, Aanchal’s approach centres on the tactile, the inherited, and the handmade. “When I first began archiving objects for my personal research, it was a simple earthen pot and I realised how memory could live inside the most ordinary things,” Aanchal shares with Manifest. What followed was an entire body of work that treated household objects not as accessories to history, but as vessels of it.

Manifest: What inspired you to begin archiving and documenting these objects?

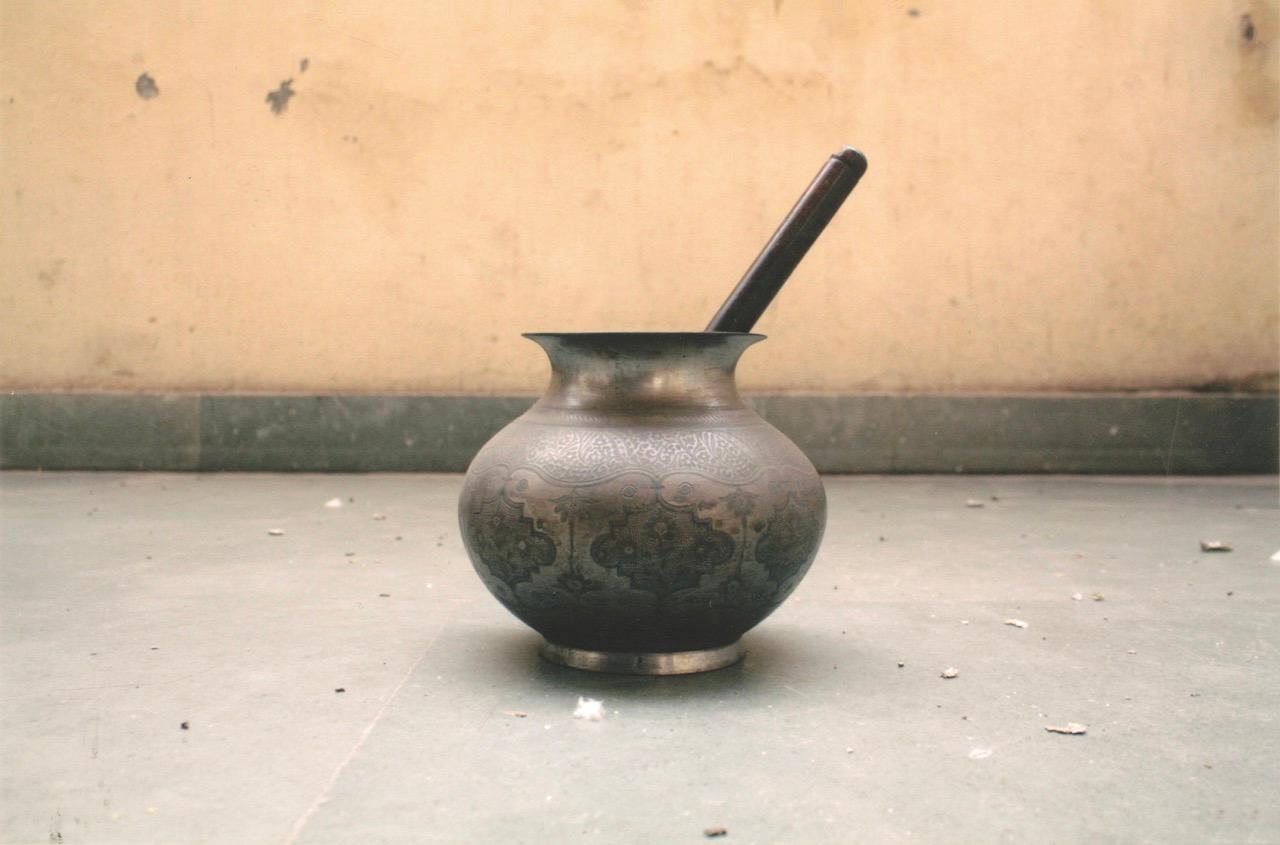

Aanchal Malhotra: “One of the first objects that I archived was a ghada, an earthen pot. It was from my nana’s [maternal grandfather] house in Lahore, Pakistan. My great-grandmother, my nana’s mother, was presented with it on her wedding day. They made lassi in it throughout their life, even after moving to Delhi. It was such an ordinary thing, but it made me realise the kinds of objects people chose to bring with them during the partition. I also came across jewellery, but there’s something about everyday objects. Do those items lose meaning because they’re used every day, or do they gain it? Over time, I’ve realised that using something every day adds to why it is considered special. And that ghada taught me that something so simple can hold a lot of meaning.”

Lassi ghara carried from Lahore to Delhi via Amritsar.Aanchal Malhotra

M: Are there any special details or anecdotes about the ghada you preserved?

AM: “My grandmother told me that the bride’s family would send these utensils to the groom’s house and they would all have the husband’s initials on them. The ghada and other utensils have her husband’s initials engraved on it. In fact, on my father’s side, all of the utensils have either my grandfather’s or my great-grandfather’s initials.”

M: Aside from this, were there other objects that stayed in the family, things that were carried, used, or remembered?

AM: “There’s a maang tikka that belonged to my grandmother’s mother. It was passed down to her in 1910, when she got married at the age of 12. She gave it to my grandmother at her wedding in 1955. Then, my grandmother gave it to me in 2017. It is still the same. It has imperfections, but I actually love that because it shows the imperfection of the hand. It wasn’t mass-produced…it can’t be copied.”

Maang tikka originally given to Lajvanti Gulyani on her wedding in Dera Ismail Khan in 1919, and passed down to Bhag Gulyani Malhotra at her wedding in Delhi in 1955.Aanchal Malhotra

M: When objects are passed down from one generation to the next, what do you think sustains their meaning?

AM: “It doesn’t matter if something is from one’s wedding trousseau or not—heirloom pieces carry the imprint of the hand. These are objects made with care and intention. Like a Phulkari bagh, a traditional embroidered shawl from Punjab, India. Each stitch means something. It was made by a woman who felt something. It was given to a young bride going to a new house, and it was accompanied by all the verbal and nonverbal cues of that occasion. Even with jewellery, I’m sure the mother would have sat with the jeweller and asked him to make it a certain way. The quality of handmade things, and even the error of the hand, shows you that a person made it with intent and meaning. To inherit such objects is a privilege.

A phulkari bagh, completed in 1931, brought from Rawalpindi to Delhi in 1947. Aanchal Malhotra

M: Is it possible for mass-produced objects to become meaningful heirlooms?

AM: “In the ’60s, my nani was living in Canada. She used to work with Avon and sold make-up and jewellery door-to-door. One of the things she got was a perfume brooch—a mass-produced, mass-consumed item at the time. But now, 60 years later, I find it beautiful, unique, and ornate. So who knows? Maybe even things we consider ordinary today will mean something in the future.”

Avon brooch belonging to Malhotra's maternal grandmother, Amrit Vij.Aanchal Malhotra

M: Lastly, what kind of objects should modern brides consider adding to their trousseau that could be passed down in the future?

AM: “I tend to invest in good-quality jewellery. I’d rather buy one piece crafted in gold than five things that are not. But that wisdom comes with age. A few years ago, I went to a jeweller and asked him to make me baalis [hoop earrings] like the bibis [women] wear in Punjab, India. He was surprised. He told me, ‘Who even asks for a design like this in today’s time?’ But I wanted that one piece because it symbolises where I come from…it means something. So it could be a piece of jewellery or a dupatta, collect things that add meaning to your life.”

This story appears in Manifest India’s Issue 04. Subscribe here for more stories like this.