- Avarna Jain,

Chairperson RPSG Lifestyle Media

Why The Doli Is Still the Heart of Every Indian Bride’s Farewell

A symbol of love, loss, and legacy, the doli carries centuries of tradition—marking a bride’s bittersweet journey…

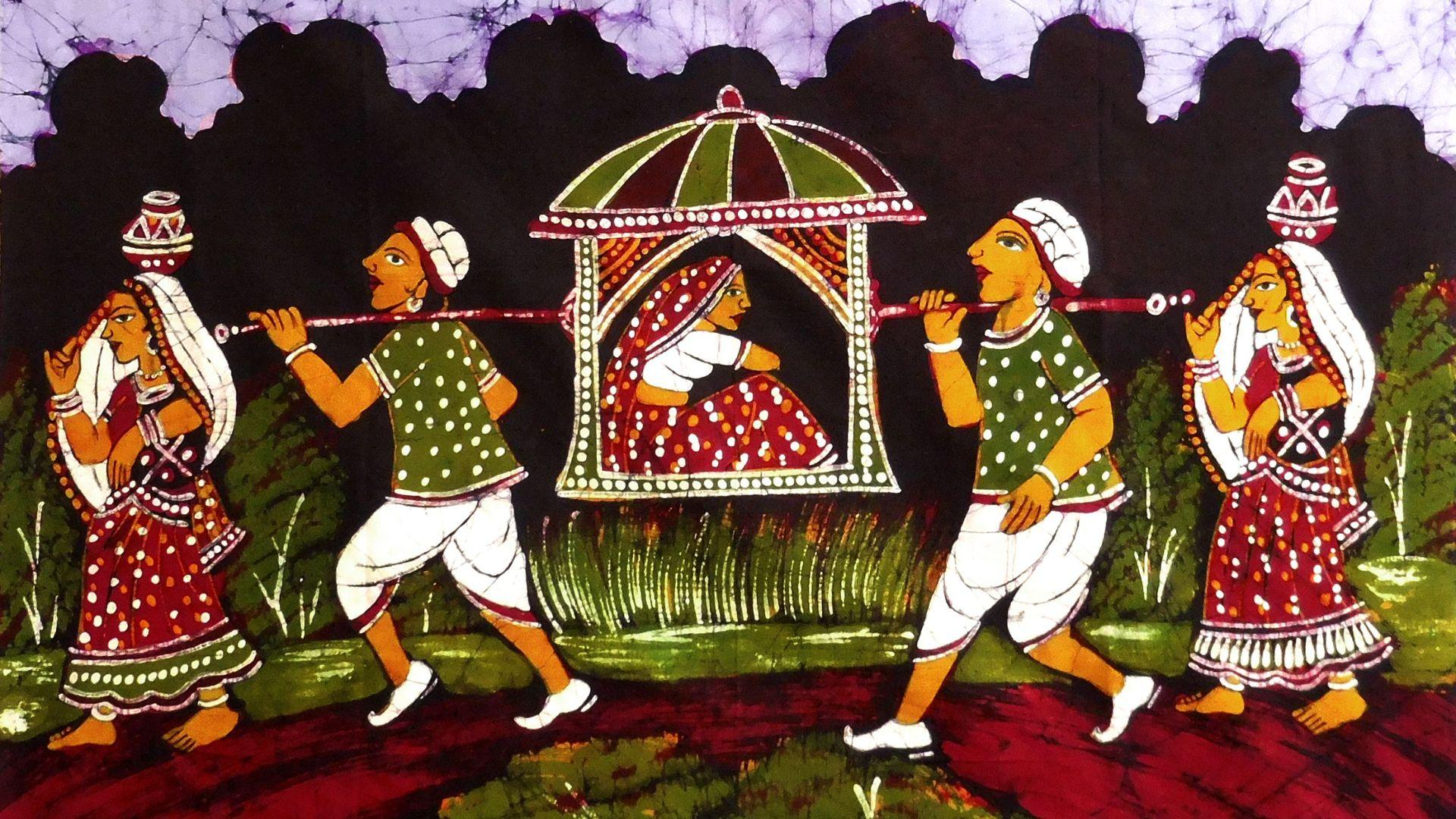

A symbol of a woman's journeyDolls of India

The doli, also known as the palanquin or the bridal carriage, is one of the most emotionally charged moments during many Indian weddings in the North. The "doli" in Indian weddings symbolises a significant and emotional change in a woman's life. It not only represents her physical relocation from her parents' home to a new home where her husband lives but also carries along a trail of expectations from society, family, and culture as well.

Palanquins, also known as palkis, dholis or dolis, have been utilised for centuries by the people of South Asia to transport and carry upper-class individuals, with brides being among the first. The usage of palanquins, both open and closed, for carrying people is evident from historical sources, and it has a lasting impact on wedding visuals and practices. As time went by, the palanquin stopped serving only weddings and began as a symbol of royalty—it was profusely adorned and accompanied with the rites of departure and arrival.

Doli: A Symbol of a Woman’s Journey

The doli (and the paired ritual often called vidaai or bidai) signifies the journey from one social household to another, symbolically. It is traditionally portrayed as a bittersweet moment: happiness for the new life, mourning for the family ties, and society's acknowledgement of the life-change the bride is entering. This emotional duality is consistently highlighted in wedding literature and cultural descriptions.

The covered palanquin in which the bride was carried historically provided privacy, protection, and a sense of honour. The escort of male relatives and attendants who lift, carry or accompany the doli underlines the family's continuing responsibility and the public nature of the transfer. The act of throwing coins, rice or small gifts as the doli departs—observed in some regional practices—is meant to shower the departing couple with prosperity and to ritualise community approval of the marriage.

Doli Ceremony Across Regions

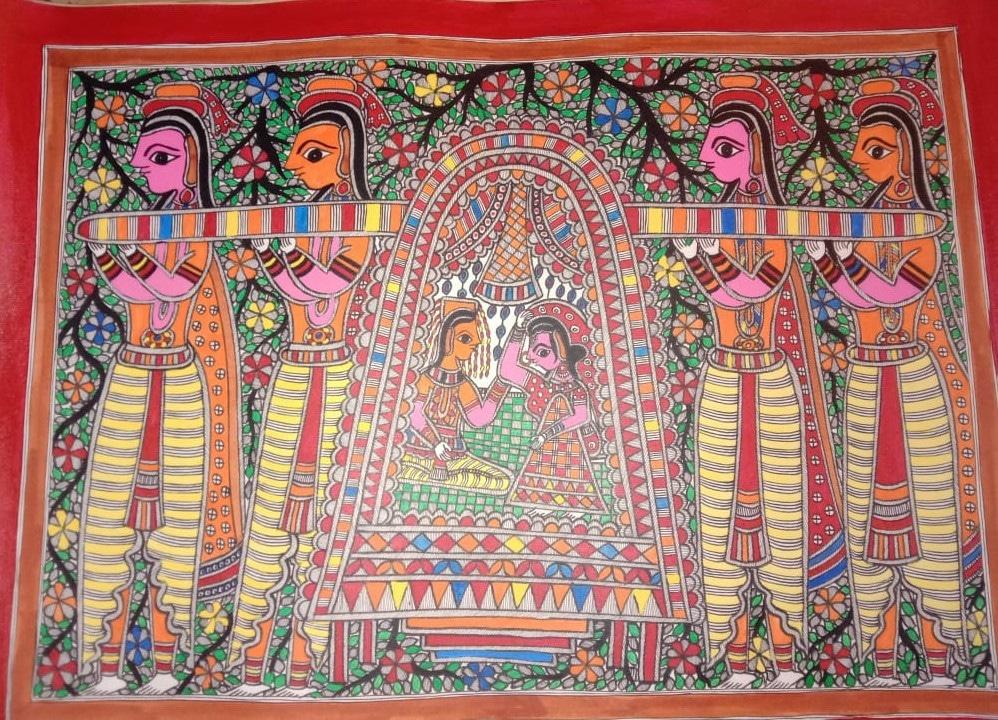

A timeless symbol of transitionInternational Indian Folk Art Gallery

In various Punjabi/Sikh wedding narratives, the doli is witnessed to the marriage ceremony and carried out with the accompaniment of specific songs, prayers, and ceremonial gestures: the bride is escorted to the doli by family elders or brothers, there might be some ritualised lifting or putting into the palki, and a sad goodbye sung via the vidaai songs of the bride. Even though the main concept—an emotional departure—is everyday, details differ in some families; the doli is literally lifted, while in others, the vehicle (or later, the car) is pushed from behind as a symbolic “sending-off”; in certain regions, coins are sprinkled, while others have separation songs predominating.

The doli and its carriers have been staples in the cultural life of South Asia for a long time. The mourning of separation and the steady bearers’ rhythm are addressed in songs, poems, and even folk verses—for instance, literary and musical references can go either way, celebrating or lamenting the palanquin’s movement, and the nineteenth- and twentieth-century poets would often use this image as a powerful motif for social change and personal loss. These artistic representations contribute to the explanation of why the doli continues to be such a striking scene in wedding photography and storytelling.

Nowadays, the dolis, in contemporary times, show up metamorphosed, turned to what ornately decorated palkis could be, for instance, a car with flowers on it or a concocted “palanquin” for just being in pictures. Urban weddings mostly make the ritual easier to perform (abbreviate, dramatise or repurpose) but still keep its symbolic essence. Meanwhile, at the same time, social critics and some of the young couples are posing a question if the doli still reflects the old notion that marriage has always been the woman's complete departure from her ancestral home, when in many cases the bride has been living independently before marriage already.

A Vehicle with a long historyVictoria and Albert Museum

This debate has caused some families to see the bride's farewell as a getting-together and linking-up rather than a parting and cutting-off process. The bride often is (either alone or with the groom) in the doli/palanquin or, in modern practice, in a fancy car. Traditionally, the close male kin (father, brothers) escort or carry the doli, and the bride's brother raises or pushes the doli, thus making his presence felt. The women in the families sing the vidaai (farewell) songs; the elders bless the couple. Sometimes, the throwing of coins or rice takes place as an act of indicating good fortune. All these elements incarnate the abstract symbolism and give it a form of a feeling that is very much recognised by the guests, and they also participate in it.

Doli, today, symbolises an intersection of personal feeling (love, loss, hope), communal rituals (blessing, witnessing), and cultural memories (historic palanquins and poetic metaphors). The couples and families who are adapting the ritual would find the most significant option in selecting the elements that truly reflect their relationship to family, independence and continuity — this could include maintaining the traditional doli, arranging a modern farewell or exchanging sad symbols for joyful ones. For cultural historians and the inquisitive observer, doli is still a striking case of how the physical object (palanquin) and social acts (departure, blessing) tell the values society holds regarding gender, family, and belonging.