- Avarna Jain,

Chairperson RPSG Lifestyle Media

How Diwali Changes Shape Across India

From battles to gods, author and mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik shares how Diwali Weaves many traditions into one shared celebration.

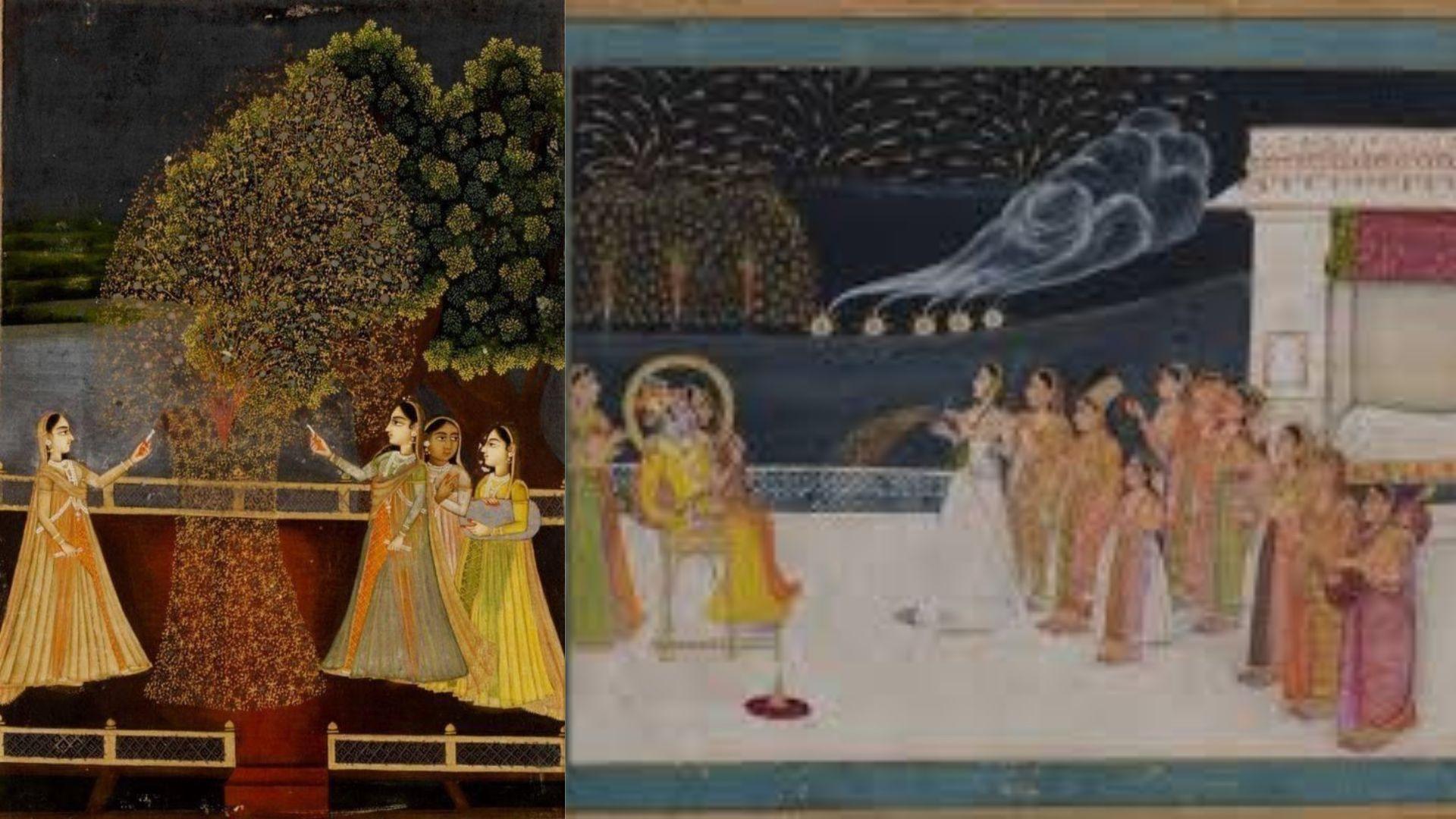

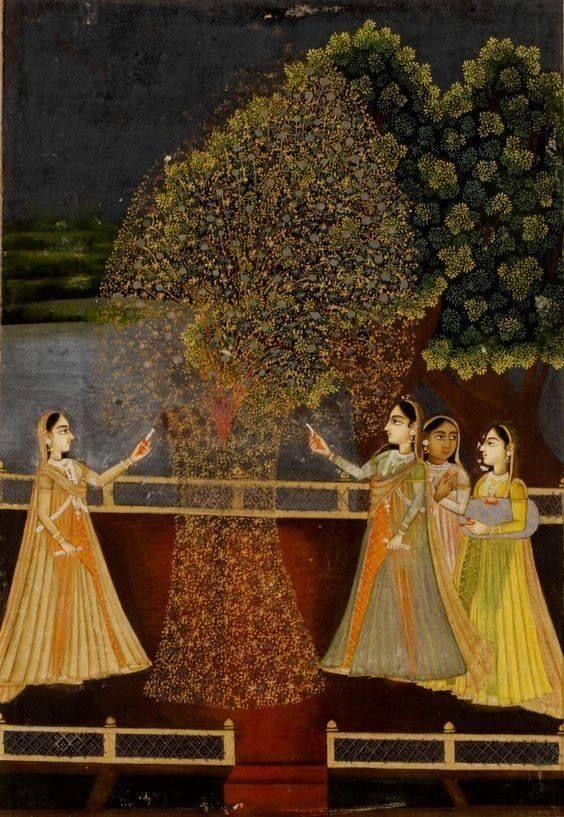

Diwali across IndiaWIKIMEDIA COMMONS; ARHUR CHURCHILL/ VICTORIA & ALBERT MUSEUM

Diwali is celebrated across India, but contrary to popular assumption, it is not a single, uniform festival. It takes very different forms depending on where you go. What most people outside India refer to as ‘Diwali’ is really the North Indian version of the festival. This is because the Gujarati popularised it, and Hindi-speaking migrant communities that carried their traditions to Europe and America. But if one travels through the rest of India, one quickly realises that Diwali is a family of festivals, with diverse local meanings.

In South India, for instance, the flavour of Diwali is markedly different. In Kerala, it is hardly a major festival at all. In Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Maharashtra, the most important rituals take place not on the new moon night of Diwali itself, but on the fourteenth day of the waning moon, known as Naraka Chaturdashi. This day commemorates the slaying of the asura Narakasura by Lord Krishna. It is also a festival tinged with romance and domestic ritual. Families begin the day with oil baths; men anoint themselves with oil mixed with vermilion. Among newlyweds, however, it is the bride who lovingly bathes and anoints her husband, re-enacting the return of Krishna from battle, when his wives bathed him. An unusual detail of the ritual involves crushing a bitter fruit, symbolising the defeat of the asura, Narakasura.

Telugu literature adds another layer to the myth. It says Krishna himself could not kill Narakasura, because of a divine condition that the asura could only die at the hands of his mother, the Earth Goddess. Unknown to Narakasura, the Earth Goddess had taken rebirth as Krishna’s wife, Satyabhama. She accompanied Krishna in this battle, and when Narakasura wounded Krishna in the battle, Satyabhama’s fury rose; she picked up a weapon and struck Narakasura down. Yet, Krishna took the credit. The story leaves one wondering whether this was a subtle reminder that women often do the hard work while men enjoy the glory, or if it was simply an instance of good storytelling.

A celebration of loveRHUR CHURCHILL/ VICTORIA & ALBERT MUSEUM

In North India, by contrast, Diwali centres increasingly on Lord Rama, whose return to Ayodhya is celebrated by lighting lamps and distributing sweets. While in the trading communities of Gujarat and Rajasthan, Goddess Lakshmi is worshipped on the new Moon night, and playing cards and gambling is considered auspicious to figure out who is favoured by fortune and skill. In Bengal, people worship Goddess Kali, the goddess of destruction. The night before is called Bhuta Chaturdashi (a night of ghosts) in Bengal, and it is something like a Hindu Halloween. Ghosts come to visit their relatives and are served food. In Odisha, especially in the Shree Jagannath Temple in Puri, Diwali takes on the colour of ancestor worship. Lamps are lit using special, dry reeds, not for Goddess Lakshmi, but to guide the souls of ancestors back home. Rice cakes are offered to them. The light shows them the way, and, after blessing their descendants, the ancestors depart. This echoes old Vedic ideas that prosperity comes from honouring the ‘pitṛas’ or deceased ancestors. In many parts of North India, two days after Diwali is Bhai Dooj or Yama Dwitiya, the day when Yama (God of death and karmic accounting) visits his sister, Goddess Lakshmi.

Across India, thus, a common theme runs through Diwali. Whether it is Rama or Krishna, Kali or Lakshmi, Narakasura or Yama, ancestors or kings—Diwali is a festival of war and triumph, fortune and death, money and renewal. After the rains, when autumn campaigns began, kings took to the battlefield. Navaratri celebrates the goddess of war. And then came the dark night of Diwali, associated variously with Lakshmi, Rama’s return, Krishna’s battles, Yama, Kali, and the ancestors. Thus, Diwali is not a single festival, but many festivals folded into one season: of gods and demons, of wealth and ancestors, of life and death.