- Avarna Jain,

Chairperson RPSG Lifestyle Media

How Indian Grooms Are Reclaiming The Traditional Headgear

From royal portraits to couture runways, traditional Indian groom headgear is having a moment...

Grooms today are reinterpreting classic headgears like the sehra or safa with unusual textures and embellishmentsInstagram

Simple, sculptural, or outright flamboyant — traditional headgear has always been integral to a groom’s look in India.

On The Runway

Season after season, they continue to be a recurring theme on the catwalk. At Lakmé Fashion Week 2024, Rohit Bal (who passed away in November) sent out models behatted in Kashmiri topis embroidered with everything from roses to birds in flight.

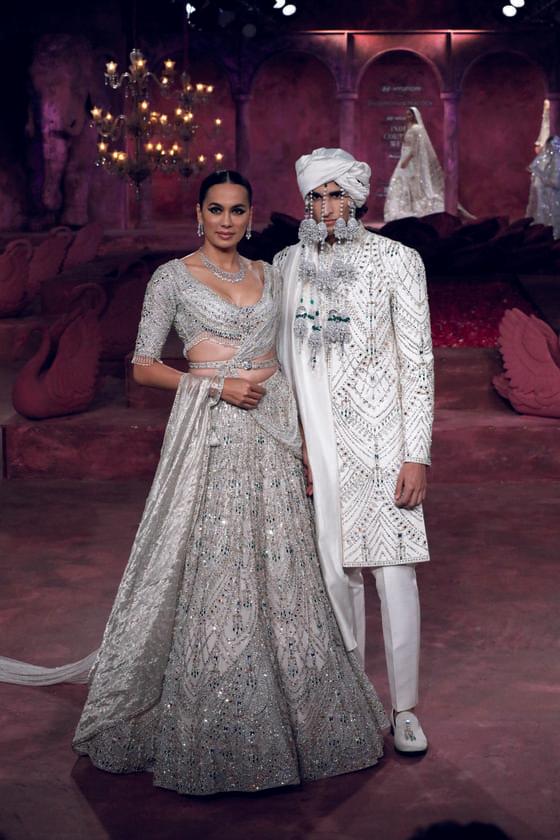

At last year's India Couture Week, designer duo Falguni and Shane Peacock created bejewelled sehras to replace floral veils. JJ Valaya reimagined the classic safa with chevron prints, while Kunal Rawal’s collection showed sleek and unisex renditions of these silhouettes. “We’ve reconceptualised sehras with minimalist designs, making them both contemporary and respectful of tradition. Similarly, our P-Cap Safa modernises the turban with elements like metal rings and subtle embellishments,” says Rawal.

SheharNishanth R

Labels like Torani have also affirmed the power of the ceremonial headpiece. Its 2019 collection Gulabi Mela, inspired by the festival Cheti Chand, was complete with boxy toppers and marked the brand’s first foray into accessories. “We used Sindhi topis, which have become a recurring brand iconography. A lot of our history often gets lost. I wanted to bring it back to the forefront,” says designer Karan Torani.

Similarly, Akshat Bansal’s brand Shehar, which opened its flagship store in Hisar last year, debuted its campaign Homecoming in 2022. The collection took cues from Haryana’s folk music ragini and leaned into pared-down safas made from Chanderi and pure satin. “The safas aren’t loud or bulky; instead, they’re elegant and lightweight.” But the story of the headgear was not always thus.

The Royal Treatment

Safas by Kunal RawalKunal Rawal

As early as the 7th century, Rajasthani men wore turbans, or safas, primarily for practical reasons: to keep their heads cool on a hot day. Today there are nearly 400 variations across the state with “the drapes changing every 100 kilometres,” according to Maayankraj Singh, who started Atelier Shikaarbagh, inspired by his grandmother Rani Urmila Raje of Dholpur. Each iteration of the safa is crafted by folding and rolling fabric in distinct ways, a tradition that later became a symbol of honour among Rajput warriors.

The transformation of the turban can be traced across India’s royal past. Maayankraj calls it the “peacock” effect, meaning the groom wants “the best finery”. Take MV Dhurandhar’s work as an example. It often depicts warrior king Shivaji wearing dome-shaped Marathi phetas. Or, Chitarman’s masterpiece of Shah Jahan, which now belongs to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The 17th-century artwork features the ruler in a purple turban set with jewels and topped with peacock feathers. The bird was a nod to the gilded Peacock Throne, which was commissioned by Shah Jahan in the same year as the portrait.

A Story in Every Fold

Falguni Shane Peacock Couture Week CollectionInstagram

JJ ValayaInstagram

A study of the history of these headpieces would be incomplete without recognising their manifestations throughout India. During a Sikh wedding ceremony (Anand Karaj), for instance, the groom wears the pagri or dastar, often paired with a jewelled brooch known as the kalgi. South India, too, has its variants. The Mysore peta, a silk and zari headdress typically worn by Kannada grooms, has been loved by both peasants and princes for more than 400 years. Its rise to prominence has been documented in several artworks. See Thomas Hickey’s oil painting of the five- year-old Krishnaraja Wadiyar III (KRW III) at his coronation in 1799. And Raja Ravi Varma’s portraits of KRW III and subsequent Wadiyar rulers wearing jewel-studded petas.

India’s craft legacy also plays a significant role. In Gujarat, grooms wear bandhani safas, which use a resist-dyeing technique with origins dating back to the Indus Valley Civilisation. Most recently, this style was seen on Anant Ambani at one of the most high-profile weddings in India. In Ladakh, the headgear takes the form of tibi (or tipi), a hat with upturned corners. And in Bengal, there’s the topor, a conical crown made from the spongy, milky- white plant material shola pith. Legend has it that when Shiva requested a special crown from master craftsman Vishwakarma, the task fell to a young artisan, Malakar. Today, the topor remains a wedding essential created by the Malakar community, whose name translates to ‘makers of garlands’.

Sacred Symbols

Torani credits this to “the spiritual aspect of weddings. In the Indian context, the bride is seen as a devi and the groom is more than just a husband-to-be; he is revered like a god. In many cultures, we call him ‘dulhe raja’ for this reason. The sanctity of this role is reflected in the groom’s clothing and accessories, from the pagdi and kalgi to the gold or silver plates tied on his head in some communities, like the Sindhis. These elements elevate him to godlike status.”

Today, the traditional headgear has been updated into an accessory that marks your vibe as a groom. “The emphasis is on customisation and personal storytelling. Whether it’s reinterpreting classics like the sehra or safa, or playing with unusual textures and embellishments, grooms today want their look to tell their story,” says Rawal. Dress codes have evolved, with many old rules no longer in play. Yet, the headgear remains a portable cue for grooms to show who they are and where they come from, a bridge between the past and the present. And a testament to a universal truth: if you craft something beautiful, it will last forever.